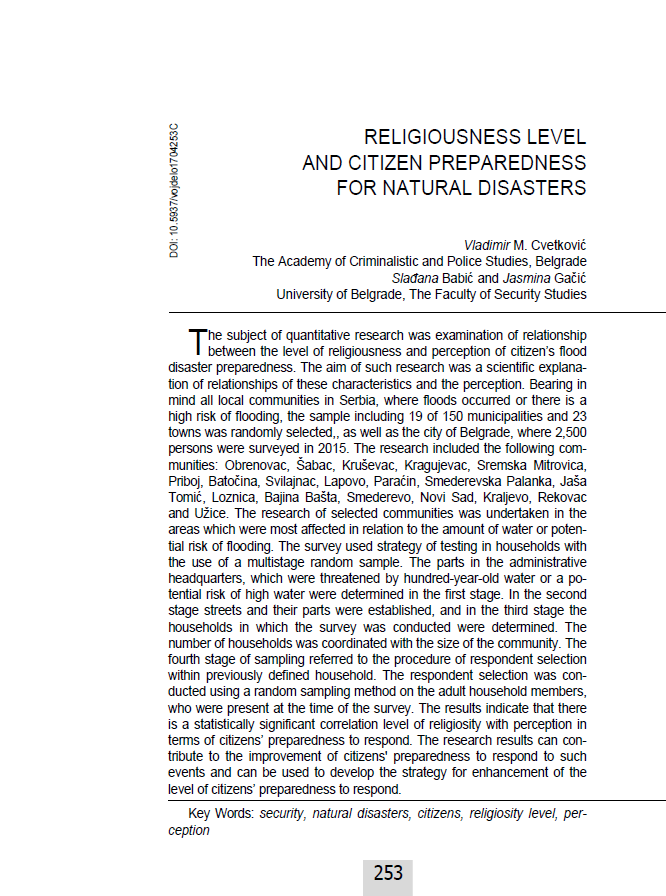

Cvetković, V., Gačić, J., & Babić, S. (2017). Religiousness level and citizen preparedness for natural disasters. Vojno delo, 69(4), 253–262.

RELIGIOUSNESS LEVEL AND CITIZEN PREPAREDNESS FOR NATURAL DISASTERS

Vladimir M. Cvetković The Academy of Criminalistic and Police Studies, Belgrade

Slađana Babić and Jasmina Gačić University of Belgrade, The Faculty of Security Studies

The subject of quantitative research was examination of relationship between the level of religiousness and perception of citizen’s flood disaster preparedness. The aim of such research was a scientific explana- tion of relationships of these characteristics and the perception. Bearing in mind all local communities in Serbia, where floods occurred or there is a high risk of flooding, the sample including 19 of 150 municipalities and 23 towns was randomly selected,, as well as the city of Belgrade, where 2,500 persons were surveyed in 2015. The research included the following com- munities: Obrenovac, Šabac, Kruševac, Kragujevac, Sremska Mitrovica, Priboj, Batočina, Svilajnac, Lapovo, Paraćin, Smederevska Palanka, Jaša Tomić, Loznica, Bajina Bašta, Smederevo, Novi Sad, Kraljevo, Rekovac and Užice. The research of selected communities was undertaken in the areas which were most affected in relation to the amount of water or poten- tial risk of flooding. The survey used strategy of testing in households with the use of a multistage random sample. The parts in the administrative headquarters, which were threatened by hundred-year-old water or a po- tential risk of high water were determined in the first stage. In the second stage streets and their parts were established, and in the third stage the households in which the survey was conducted were determined. The number of households was coordinated with the size of the community. The fourth stage of sampling referred to the procedure of respondent selection within previously defined household. The respondent selection was con- ducted using a random sampling method on the adult household members, who were present at the time of the survey. The results indicate that there is a statistically significant correlation level of religiosity with perception in terms of citizens’ preparedness to respond. The research results can con- tribute to the improvement of citizens’ preparedness to respond to such events and can be used to develop the strategy for enhancement of the level of citizens’ preparedness to respond.

Key Words: security, natural disasters, citizens, religiosity level, per- ception

Introduction

Exploring academic works and government reports connected with human security,1 security threats seem so horrible and so endless: war threats, war, or- ganised crime , social disagreements, political repression, economic crises, long-term changes in the environment, poverty, mass migrations and internal displacement, terro- rism, technological and natural disasters, etc. The central part of the topic of human security is based on these threats, their inclusion or exclusion from the human security program, their gradation and prioritization. In the past decades, vulnerability to natural hazards took precedence over technological and other hazards threatening the community. According to the data from the OFDA/CRED International Disasters Data- base (EM-DAT), the number of natural disasters appears to be increased worldwide. In the decade 1900-1909, natural disasters occurred 73 times, but in the period 2000-2005 the number of occurrences rose to 2,788. Furthermore, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies reported in 2004 that 231,764 people were killed

by disasters in Asia from 1972 to 1996. (Kusumasari, Alam & Siddiqui, 2010)

Studying natural disasters (Jakovljević, Cvetković & Gačić, 2015) from the aspect of governing, the researchers have dealt directly/indirectly with the issue of preparedness as a theoretical concept and a practical discipline (Cvetković, 2015, 2016b, 2016c; Cvetković, Gačić & Jakovljević, 2015). Russell and associates (Russell, Goltz & Bourque, 1995) view preparedness as any preventive activity done by an individual, a household, a community or a state before and during a disaster, including obtaining, dealing with and distributing significant information on preventive activities, getting plans, supplies and equipment. In the theory of disasters, researchers looked at the influence of different factors on the prepar- edness of citizens to respond: sex (Becker, 2011), age (Levac, Toal-Sullivan & OSullivan, 2012), fear (Dooley, Catalano, Mishra & Serxner, 1992), perception of risk (Mulilis, Duval & Rogers, 2003), knowledge/education (Çakın, Petal, Sezan & Türkmen, 2006), etc. Deter- mining the influence of different factors on the preparedness of citizens to react is important because of planning strategy and campaigns for promotion of preparedness, and emer- gency and rescue services actions, as well (Cvetković, 2016a; Cvetković & Gačić, 2016).

Religiousness could be connected to spiritual health, as the part of holistic model of health: physical, social, emotional, intellectual and spiritual health, thus enhancing the motivation for community and self-protection. (O’Donnell, 2009) The frequently asked

1 Despite the fact that the needs of this work are not such that request deeper consideration of the problem of defining the human security, we regard it as necessary to explain our approach to this phenomenon. The term “human” indicates the focus on an individual and the term “security” refers to the need of protection against threats and the creation of safe environment. Therefore, we consider “human security” as the new, incoming concept dealing primarily with the security of people and individuals rather than the security of state territory and which is based on the survival, everyday life and dignity of human beings. The word “survival“ reflects the security aspect and means the protection against an attack on physical integrity, as well as the satisfaction of basic needs; the word “dignity“ refers to the strong bond between human rights and human security, whereas the word “everyday life“ indicates the specific nature of human security, ie. it goes further than achieving security and dignity, connec- ting safety problems with the issues of living in communities and families, enlarging the scope of security against violent threats problems to yet unexplored fields. This leads to further examination of human security as “designed to include management and protection of political communities into the broader scope of concern for achieving individual prosperity and invulnerability. In that context, we have dealt with the abovementioned topic in this work.

question about percentage of religious citizens of Serbia is not so simple to answer. The research survey of religiousness of citizens of Serbia and their relation to the European Union with the sample of 1,219 examinees shows that a very high percentage of citizens express themselves as believers (93%) (Bigović & Bone, 2011). According to the results, 3.1% of examinees are absolutely unreligious, 7.8% are unreligious to a certain extent, 57,9% are neither religious nor unreligious, 20.7% of examinees are religious to a certain extent, and finally 7% of examinees are absolutely religious. According to the results of cross-examination, there were more unreligious males than females. The aim of our in- vestigation was to search the influence of religiousness on the preparedness of citizens to respond to a natural disaster caused by flood in the Republic of Serbia.

Methodology of research

For the purpose of conducting the survey, statistical method and the method of em- pirical generalization stratified the local communities with high and low risk of flooding in the Republic of Serbia. Thus, the stratum was obtained, i.e. the population that consisted of adult residents of local communities where flooding took place or a risk of flooding existed. Using the random sampling method, 19 out of 154 communities with the induced risk of flooding were chosen from the resulting stratum. The research included the follow- ing communities: Obrenovac, Šabac, Kruševac, Kragujevac, Sremska Mitrovica, Priboj, Batočina, Svilajnac, Lapovo, Paraćin, Smederevska Palanka, Jaša Tomić, Loznica, Baji- na Bašta, Smederevo, Novi Sad, Kraljevo, Rekovac and Užice. The multilevel random sampling was used in the further procedure. The parts in the administrative headquar- ters, which were threatened by hundred-year-old water or by a potential risk of high wa- ter were determined in the first stage. In the second stage streets and their parts were established, and in the third stage the households in which the survey was conducted were determined. The number of households was coordinated with the size of the com- munity. The fourth stage of sampling referred to the procedure of respondent selection within previously defined household. The respondent selection was conducted using a random sampling method on the adult household members, who were present at the time of the survey. 2,500 citizens were involved in the survey (Table 1).

Municipality

Total area in km2

Settlements

Population

Number of households

Number of respondents

Percentage (%)

Table 1 – Structure overview of features of local communities in which citizen surveys are conducted

|

Obrenovac |

410 |

29 |

72,682 |

7,752 |

178 |

7.71 |

|

Šabac |

797 |

52 |

114,548 |

19,585 |

140 |

6.06 |

|

Kruševac |

854 |

101 |

131,368 |

19,342 |

90 |

3.90 |

|

Kragujevac |

835 |

5 |

179,417 |

49,969 |

91 |

3.94 |

|

Sremska Mitrovica |

762 |

26 |

78,776 |

14,213 |

174 |

7.53 |

|

Priboj |

553 |

33 |

26,386 |

6,199 |

122 |

5.28 |

Municipality

Total area in km2

Settlements

Population

Number of households

Number of respondents

Percentage (%)

Batočina 136 11 11,525 1,678 80 3.46

Svilajnac 336 22 22,940 3,141 115 4.98

Lapovo 55 2 7,650 2,300 39 1.69

Paraćin 542 35 53,327 8,565 147 6.36

Smed. Palanka 421 18 49,185 8,700 205 8.87

Sečanj – Jaša Tomić 82 1 2,373 1,111 97 4.20

Loznica 612 54 78,136 6,666 149 6.45

Bajina Bašta 673 36 7,432 3,014 50 2.16

Smederevo 484 28 107,048 20,948 145 6.28

Novi Sad 699 16 346,163 72,513 150 6.49

Kraljevo 1,530 92 123,724 19,360 141 6.10

Rekovac 336 32 10,525 710 50 2.16

Užice 667 41 76,886 17,836 147 6.36

Total 10,784 634 1,500,091 283,602 2,500 100

Table 2 gives a detailed structure overview of the interviewed citizens. The imple- mentation of these sampling techniques provided solid representation of the sample; the sample size provided reliability in the conclusion regarding the basic set – population.

Variables

Categories

Frequency

Percentage (%)

Table 2 – Structure overview of the sample of the interviewed citizens

|

Male |

1,244 |

49.8 |

|

Female |

1,256 |

50.2 |

|

From 18 to 28 years |

711 |

28.4 |

|

From 28 to 38 years |

554 |

22.2 |

|

From 38 to 48 years |

521 |

20.8 |

|

From 48 to 58 years |

492 |

19.7 |

|

From 58 to 68 years |

169 |

6.8 |

|

Over 68 years |

53 |

2.2 |

|

Primary school |

180 |

7.2 |

|

Three-year-long secondary education |

520 |

20.8 |

|

Four-year-long secondary education |

1,032 |

41.3 |

|

College (three years) |

245 |

9.8 |

|

Faculty (four years) |

439 |

17.6 |

|

Master |

73 |

2.9 |

|

Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) |

11 |

0.4 |

Gender

Years of age

Level of education

Variables

Categories

Frequency

Percentage (%)

|

Single |

470 |

18.8 |

|

Related |

423 |

16.9 |

|

Engaged |

67 |

2.7 |

|

Married |

1,366 |

54.6 |

|

Divorced |

99 |

4.0 |

|

Widow / widower |

75 |

3.0 |

|

Up to 2 km |

1,479 |

59.2 |

|

From 2 to 5 km |

744 |

29.8 |

|

From 5 to 10 km |

231 |

9.2 |

|

Over 10 km |

46 |

1.8 |

|

Up to 25,000 dinars |

727 |

29.1 |

|

Up to 50,000 dinars |

935 |

37.4 |

|

Up to 75,000 dinars |

475 |

19.0 |

|

Over 90,000 dinars |

191 |

7.6 |

Marital status

Distance of household from the river

Incomes

Results

Results of χ–square test of independency (χ2) have showed that there is a statisti- cally significant correlation between the level of religiousness and the following variables: preventive measures (p = 0.03 < 0.05, v = 0.072); engaged in the area (p = 0.010 < 0.05, v = 0.076); engaged in the reception centre (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.135); prolonged raining (p = 0.034 < 0.05, v = 0.068); increasing the level of rivers (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.098); media reports (p = 0.007 < 0.05, v = 0.079); the level of preparedness (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.078). On the other side, significant correlation with the following variables is not observed statistically: visits to the flooded sites (p = 0.100 < 0.05, v = 0.059), financial means (p = 0.090 < 0.05, v = 0.060) (Table 3). According to the obtained results, the highest percentage of the citizens who are not religious to a certain extent would offer help to the endangered citizens in the area (28.9%), would help in one of the reception centers (10.8%), thoughts of preparedness are aroused by media reports (45.2%), do nothing to prepare themselves to respond (66.2%); religious people to a certain extent are aroused to think about preparedness to respond by the increase of water level (41.5%), have taken preventive measures in order to lessen the flood effects (21%), are still not ready, but are going to start preparations next month (14.3%), have recently started preparations (11.8%); absolutely religious citizens are aroused to think about preparedness to respond by prolonged raining (48.2%), are still not ready, but are going to do it in the next six months (15.2%), have been preparing for at least 6 months (7.9%). On the other hand, the smallest percentage of unreligious citizens to a certain extent are aroused to think about preparedness to respond by the increase of water level (26%), have been preparing for at least 6 months (1.4%); neither religious nor unreligious

citizens would help in one of the reception centers, have recently started preparations, are still not ready, but are going to start preparations next month; religious citizens to a certain extent have taken preventive measures in order to lessen the flood effects (10.2%), would offer help to the endangered citizens in the area (14.3%); absolutely reli- gious citizens are aroused to think about preparedness to respond by prolonged raining (35%), media reports (25.3%), are still not ready, but are going to do it in the next six months (10.4%), do nothing to prepare themselves to respond (52.6%).

Тable 3 – Results overview of Х-square test of independency (χ2) of religiousness level and mentioned variables on perception of preparedness to respond

|

value |

df |

Asymp. Sig. (2 – sided) |

Cramers V |

|

|

Preventive measures |

22,899 |

8 |

.003* |

.072 |

|

Financial means |

8,055 |

4 |

.090 |

.060 |

|

Engaged in the area |

13,302 |

4 |

.010* |

.076 |

|

Engaged in the reception center |

41,751 |

4 |

.000* |

.135 |

|

Visit to the flooded sites |

7,769 |

4 |

.100 |

.059 |

|

Prolonged raining |

10,433 |

4 |

.034* |

.068 |

|

Increase of river level |

21,857 |

4 |

.000* |

.098 |

|

Media reports |

13,993 |

4 |

.007* |

.079 |

|

Level of preparedness |

53,994 |

20 |

.000* |

.078 |

* statistically significant correlation – p ≤ 0.05

One-way analysis of variance (оne-way ANOVA) examines the influence of religiou- sness level on dependant continual variables the perception of preparedness to respond. Subjects are divided in 5 groups according to the level of religiousness (absolutely unre- ligious, unreligious to a certain extent, neither religious nor unreligious, religious to a cer- tain extent, absolutely religious).

According to the results, there is a statistically significant difference among mean val- ues in mentioned groups with the following dependant continual variables: preparedness of local communities (F = 2.79, p = 0.026, ek = 0.0070); preparedness of the state (F = 4.75, p = 0.001, ek = 0.0044); the importance of taken measures (F = 3.77, p = 0.005, ek = 0.0063); I do not have time for that (F = 4.57, p = 0.001, ek = 0.0061); It will not influence the secu- rity (F = 2.41, p = 0.049, ek = 0.0037); I am not able (F = 5.69, p = 0.000, ek = 0.0087); I do

not have support (F = 3.17, p = 0.013, ek = 0.0054); I can’t prevent it (F = 4.70, p = 0.001, ek = 0.0067); neighbors (F = 3.22, p = 0.013, ek = 0.0051); non-governmental humanitar- ian organizations (F = 4.93, p = 0.001, ek = 0.0082); international humanitarian organiza- tions (F = 4.57, p = 0.001, ek = 0.0077 – little influence); religious community (F = 15.37, p = 0.000, ek = 0.0243; police (F = 5.59, p = 0.000, ek = 0.0094); ВСЈ (F = 2.71, p = 0.030,

ek = 0.0051); awareness (F = 4.24, p = 0.002, ek = 0.0070); state institutions work (F = 2.70, p = 0.031, ek = 0.0038); citizens from the flooded area (F = 6.31, p = 0.000, ek = 0.0086); lack of time (F = 7.67, p = 0.000, ek = 0.0115); too expensive (F = 3.97, p = 0.004, ek = 0.0071); police efficiency (F = 2.96, p = 0.020, ek = 0.0038); efficiency of firefighters and rescue bri- gades (F = 3.17, p = 0.014, ek = 0.0058); and medical emergency service efficiency (F = 2.60, p = 0.036, ek = 0.0047) (Tabela 2).

Citizens who are neither religious nor unreligious showed higher level of individual preparedness to respond to flood compared to absolutely religious citizens; citizens who are absolutely unreligious showed higher level of state and local community prepared- ness to respond to flood compared to absolutely religious. Regarding the barriers of pre- paredness, citizens who are absolutely unreligious point out to a greater extent the rea- son like “I don’t have time for that” and “I don’t have the local community support” for not taking preparedness measures compared to citizens who are exceptionally religious. On the other hand, citizens who are exceptionally religious point out to a greater extent “I think that it won’t influence my personal security nor the security of my family” for not taking preparedness measures compared to citizens who are absolutely unreligious. Citizens who are absolutely unreligious point out to a greater extent “I am not able to do that” as a reason for not taking preparedness measures compared to citizens who are absolutely religious. Citizens who are absolutely unreligious point out to a greater extent “I can’t prevent the consequences in any way” as a reason for not taking preparedness measures compared to citizens who are absolutely religious. From now on, regarding the expectancy of help in a situation of natural disaster, citizens who are absolutely unrelig- ious rely on household members’ and neighbors’ help to a greater extent compared to citizens who are absolutely religious. On the other hand, citizens who are exceptionally religious rely on non-governmental humanitarian organizations’ help to a greater extent compared to citizens who are absolutely unreligious. Citizens who are neither religious nor unreligious rely on non-governmental humanitarian organizations’ help to a greater extent compared to citizens who are absolutely unreligious. Citizens who are unreligious to a certain extent point out to a greater extent “I expected citizens from the flooded area to be engaged in the first place” as a reason for not helping the endangered people with the flood consequences compared to citizens who are absolutely unreligious. Citizens who are absolutely unreligious point out to a greater extent “I didn’t have time” as a rea- son for not helping the endangered people. Citizens who are unreligious to a certain ex- tent estimate the efficiency of police reaction to a greater extent compared to citizens who are religious to a certain extent.

Results of χ–square test of independency (χ2) have showed that there is a statistically significant correlation between the level of religiousness and the following variables: knowl- edge about flood (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.090); evacuation (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.074); education at school (p = 0.001 < 0.05, v = 0.076); education in a family (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.087); education at work (p = 0.038 < 0.05, v = 0.061); assent to evacuation (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.114); help – the elder, the invalids (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.087); neighbors – individually (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.081); flood risk chart (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.087); potential infection (p = 0.018 < 0.05, v = 0.064); water valve (p = 0.031 < 0.05, v = 0.060); electricity switch plug (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.091); handling water valve (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.079); handling gas valve (p = 0.009 < 0.05, v = 0.074); handling electricity switch plug (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.087); information by the house- hold members (p = 0.030 < 0.05, v = 0.069); information by neighbors (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.120); information by friends (p = 0.001 < 0.05, v = 0.088); information from family (p = 0.001 < 0.05, v = 0.093); information through the informal system (p = 0.002 < 0.05, v = 0.088); information at work (p = 0.001 < 0.05, v = 0.090); information on TV (p = 0.004

< 0.05, v = 0.082); information by radio (p = 0.008 < 0.05, v = 0.078); information by

press (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.121); information by the Internet (p = 0.005 < 0.05, v = 0.081); wish to attend a training course (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.079); education over video games (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.155); education over the Internet (p = 0.044 < 0.05, v = 0.066); education over lectures (p = 0.002 < 0.05, v = 0.088).

On the other hand, statistically significant correlation is not determined with variables: the elder, the handicapped (p = 0.058 < 0.05); gas valve (p = 0.092 < 0.05); familiarity with security procedures (p = 0.064 < 0.05); official warning (p = 0.0051 < 0.05); informa- tion at school (p = 0.658 < 0.05); information at faculty (p = 0.563 < 0.05); information in a religious community (p = 0.503 < 0.05); completed training course (p = 0.237 < 0.05); education by TV (p = 0.566 < 0.05); education by radio (p = 0.286 < 0.05); informal sys- tem (p = 0.933 < 0.05) (Tabela 3)

According to the obtained results, the greatest percentage of citizens who are unre- ligious to a certain extent know what is flood (90.7%), would evacuate in a reception cen- ters (9.5%), point out that a person at school talked about floods (33.8%), received in- formation on floods on TV (67.5%), would like to attend training course for treating such natural disasters (49.3%), would like to be educated over the Internet (29.3%); neither religious nor unreligious citizens would evacuate to neighbors (15.8%), to friends (38.6%), would evacuate in the case of incoming flood wave (94.9%), are familiar what kind of help the elders, the invalids and the infants need (58.6%), think that their neighbors can rescue themselves on their own in the case of flood (47.8%), would like to be educated on floods through video games (8.2%); citizens who are religious to a cer- tain extent would evacuate to reception centers (14.2%), are familiar with handling elec- tricity switch plug (74.3%), gained information on floods at work (16.3%), by press (36.5%), over the Internet (31.5%), would like to be educated on lectures (32.9%), are familiar with the flood risk chart of a local community (19.4%), gained information on floods from household members (36.2%), through informal system of education (10.9%); absolutely religious citizens would evacuate to higher floors of the house (49%), point out that a household member talked about the floods (45.1%), someone at work talked (33.3%), are familiar with viruses and infection threatening after the flood (48.8%), are familiar with where the water valve is (85.3%), electricity switch plug (80.8%), know how to operate water valve (78.3%), gas valve (53.2%), gained information on floods from neighbors (31.2%), from friends (20.4%), family (15.9%), by radio (18.6%);

Results of χ–square test of independency (χ2) have showed that there is a statisti- cally significant correlation between the level of religiousness and the following variables: household supplies (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.116); food supplies (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.146 –a little influence); water supplies (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.225); radio transistor (p = 0.005 < 0.05, v = 0.111); a torch (p = 0.007 < 0.05, v = 0.107); a shovel (p = 0.000 <

0.05, v = 0.132); a hack (p = 0.050 < 0.05, v = 0.088); a hoe and a spade (p = 0.012 < 0.05, v = 0.102); initial fire extinguisher (p = 0.028 < 0.05, v = 0.097 – a little influence); supplies renewal (p = 0.001 < 0.05, v = 0.103); supplies in a vehicle (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.078); first aid kit in a house (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.103); first aid kit in a vehicle (p = 0.047 < 0.05, v = 0.066); first aid kit– easily accessible (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.086); acting plan (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.112); discussion about a plan (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.089 – a little influence); copies of documents (p = 0.000 < 0.05, v = 0.109); insur- ance (p = 0.017 < 0.05, v = 0.064).

According to the obtained results, absolutely unreligious citizens have food supplies for two days (21.7%); to a certain extent unreligious citizens have food supplies for four days (43.2%), water supplies for one day (59.5%), never renew supplies (57.1%); neither reli- gious nor unreligious citizens have a radio transistor (19.7%), a shovel (36.4%), an initial fire extinguisher (15.9%); religious citizens to a certain extent have supplies in the case of flood (35.3%), have water supplies for two days (41%), a radio transistor (41.8%), a hack (29.2%), renew supplies once a month (43.5%), keep a first aid kit at an easily accessible place (73.2%), have a written plan for action in the case of flood (3.3%), have unwritten plan for action in the case of flood (17.7%); absolutely religious citizens have food supplies for four days (77.3%), water supplies for four days (66%), a shovel (43.6%), renew supplies once a year (24.2%), have supplies in a vehicle (10.4%), first aid kit at home (61.3%), dis- cuss about the plan of action (19.6%), have copies of important personal, financial docu- ments (32.2%), insure household against flood consequences (10.5%).

Conclusion

Taking into account the correlation between the level of religiousness and prepared- ness of citizens to respond, the following conclusions are reached:

- statistically significant correlation is determined among the level of religiousness and the following category variables regarding the perception of preparedness: preven- tive measures, engagement on the site, engagement at the reception centres, prolonged rain, increased level of rivers, media reports, level of preparedness. Furthermore, statis- tically significant correlation is determined with the following continual variables: prepar- edness of a local community, preparedness of a state, the importance of preventive measures, I don’t have time for that, It won’t influence the security, I am not able, I don’t have support, I can’t prevent, neighbors, non-governmental humanitarian organizations, international humanitarian organizations, religious communities, police, firefighter and rescue brigade, awareness, state institution work, citizens from the flooded area, lack of time, too costly, efficiency of police, firefighter brigades and urgent medical services;

- statistically significant correlation is determined among the level of religiousness and the following variables regarding knowledge about flood, evacuation, education at school, educa- tion in a family, education at work, assent to evacuation, help to the elders, the invalids, neighbors – individually, flood risk chart, potential infection, water valve, electricity switch plug, handling water valve, handling gas valve, handling electricity switch plug, information by household members, information by neighbors, information by friends, information by family, information through informal system, information at work, information on TV, information by radio, information by the press, information over the Internet, wish to attend a training course, education over video games, education over the Internet, education on lectures;

- statistically significant correlation is determined among the level of religiousness and the following variables on supplies: supplies at home, food supplies, water supplies, radio transistor, torch, a shovel, a hack, a hoe and a spade, initial fire extinguisher, re- newal of supplies, supplies in a vehicle, first aid kit at home, first aid kit in a vehicle, first aid kit -easily accessible, acting plan, discussion about the plan, copies of documents, insurance.

References

-

Becker, P. (2011). Whose risks? Gender and the ranking of hazards. Disaster Prevention and Management, 20(4), 423-433.

-

Bigović, R., & Henri, B. (2011). Religioznost građana Srbije i njihov odnos prema procesu Evropskih integracija. Beograd: Hrišćanski kulturni centar, Centar za evropske studije, Fondacija Konrad Adenauer.

-

Çakın, Y., Petal, M., Sezan, S., & Türkmen, Z. (2006). Public Education–Disaster Prepa- redness Education Program in Turkey. Paper presented at the poster), 100th Anniversary Ear- thquake Conference, CA: San Fransisco.

-

Cvetković, V. (2015). Spremnost za reagovanje na prirodnu katastrofu – pregled literature. Bezbjednost, policija i građani, 1-2/15(XI), 165-183.

-

Cvetković, V. (2016a). Policija i prirodne katastrofe. Beograd: Zadužbina Andrejević.

-

Cvetković, V. (2016b). Strah i poplave u Srbiji: spremnost građana za reagovanje na prirod- ne katastrofe. Zbornik matice srpske za društvena istraživanja, 155(2/2016).

-

Cvetković, V. (2016c). Uticaj motivisanosti na spremnost građana Republike Srbije da rea- guju na prirodnu katastrofu izazvanu poplavom. Vojno delo, 3/2016.

-

Cvetković, V., & Gačić, J. (2016). Evakuacija u prirodnim katastrofama. Beograd: Zadužbi- na Andrejević.

-

Cvetković, V., Gačić, J., & Jakovljević, V. (2015). Uticaj statusa regulisane vojne obaveze na spremnost građana za reagovanje na prirodnu katastrofu izazvanu poplavom u Republici Srbiji. Ecologica, 22(80), 584-590.

-

Dooley, D., Catalano, R., Mishra, S., & Serxner, S. (1992). Earthquake Preparedness: Predictors in a Community Survey1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 22(6), 451-470.

-

Jakovljević, V., Cvetković, V., & Gačić, J. (2015). Prirodne katastrofe i obrazovanje. Beo- grad: Univerzitet u Beogradu, Fakultet bezbednosti.

-

Kusumasari, B., Alam, Q., Siddiqui, K. (2010). Resource capability for local government in managing disasters, Disaster Prevention and Management, Vol. 19, No. 4, 438-451.

-

Levac, J., Toal-Sullivan, D., & OSullivan, T. L. (2012). Household emergency prepared- ness: a literature review. Journal of community health, 37(3), 725-733.

-

Mulilis, J. P., Duval, T. S., & Rogers, R. (2003). The Effect of a Swarm of Local Tornados on Tornado Preparedness: A Quasi‐Comparable Cohort Investigation1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33(8), 1716-1725.

-

O’Donnell M. P. (2009) Definition of Health Promotion 2.0: Embracing Passion, Enhancing Motivation, Recognizing Dynamic Balance, and Creating Opportunities. American Journal of Health Promotion, 24(1).

-

Russell, L. A., Goltz, J. D., & Bourque, L. B. (1995). Preparedness and hazard mitigation actions before and after two earthquakes. Environment and Behavior, 27(6), 744-770.